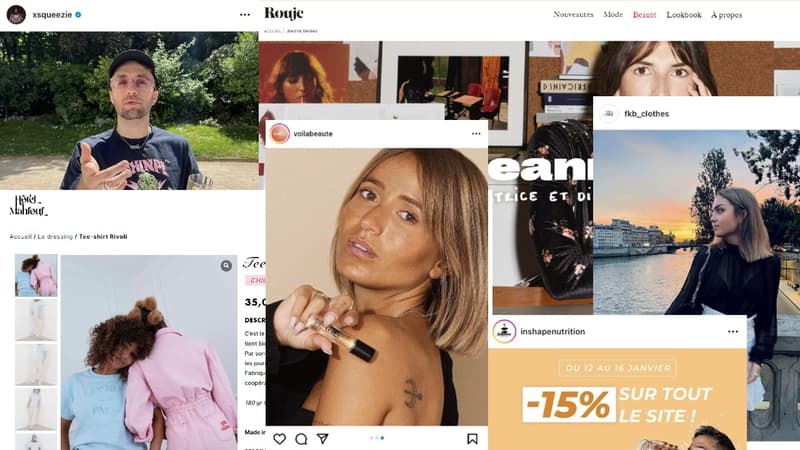

Yoko Shop, Hôtel Mahfouf, Rouje, Martine Cosmetics, Lockd, Inshape Nutrition… The list of brands created by influencers could be extended by many lines. Since the rise of content creation in the 2010s (especially on Instagram), many personalities have started a parallel business to social networks, which often translates into online stores.

This is, for example, the case of Camille Callen, known under the pseudonym Noholita. The “lifestyle” influencer is now involved to varying degrees in five other activities, across various companies.

“More entrepreneur than influencer”

Followed by a million people on Instagram, the designer even now calls herself “more of an entrepreneur than an influencer.” Her activities with her cosmetics brand (called Voilà) and her offices in the heart of Paris, which she rents out for events, take more time than creating content on social media.

And yet: it is for the moment still the influence that allows him to earn a living. “I never got paid with any of my companies,” says Camille Callen. However, she pays four full-time employees with the income from these businesses.

Ultimately, the 30-year-old would like to see “the relationship reversed.” “Influence is not eternal but I want to take advantage of it to do what interests me,” adds the designer. And she’s not the only one who thinks this job is short-lived.

Kimberly Bailly, who became an influencer after having some success on Tiktok, also finds that “in such an uncertain job, it’s nice to have something on the sidelines.” Seeing her power of recommendation to her community prompted her to launch her clothing brand, FKB, and pursue it full-time. She therefore left her business school after three years of study.

“dying” uncertainty

The young woman describes the uncertainty surrounding this profession as “dying”: “At one point it depended on my statistics. If I didn’t do many (views) it was wrong.” She is very aware of the importance of constantly renewing herself on social networks, given the evolution of algorithms and uses.

A phenomenon that many creators have already denounced, some reaching burnout. “Ten years ago YouTube was the network where everything happened, today it is TikTok”, he cites as an example.

On this network, she regularly shows off her outfits and clothing purchases, in videos that are sometimes viewed hundreds of thousands of times. Kimberly Bailly therefore watches with concern the discussions surrounding the Chinese platform and its possible regulation, or even ban.

In France, a commission of inquiry was created in the Senate in March to study “the use of the TikTok social network, its data exploitation, its influence strategy.” In the United States, a possible ban on the application has been debated for several months. In such a situation, “diversifying can only be a security,” says Kimberly.

Precarious workers?

Highly correlated with brand propositions, cash inflows can also vary greatly from month to month for content creators. Influencers like Kimberly or Camille who make a living from their activity are also very minority in the sector.

“Although they are very visible, we find ourselves with an elite work organization that manages to get by and finds relatively important margins of comfort in life, but for ordinary influencers, the reality is quite different,” says the sociologist. Joseph Godefroy, author of a thesis on the “put to work” of influencers.

For everyone, “the situation is precarious because there is no long-term commitment from the brands”, which establish collaboration contracts for a maximum of one year, explains the sociologist.

Launches and flops

Its subscribers constitute a “future customer base” for their own entrepreneurial ventures, explains Alice Audrezet, professor-researcher of marketing at the French Fashion Institute. But having a strong following on the networks is not enough to ensure the success of a project. Poor management, unfavorable economic conditions, unpopular products… The reasons for these failures -rarely explained- are numerous.

In January 2022, the youtuber Sananas announced in a video the end of her cosmetics company Otrera, launched just six months earlier. She had experienced many logistical problems, with some orders validated multiple times that needed to be canceled and refunded. In a video published in January 2023, the videographer assures that the closure of her business “was not a matter of money” but of “health”.

In March, YouTuber Amixem’s company, Spacefox, announced that it would stop producing clothing and focus on its bracelets containing meteorite fragments. In its press release, Spacefox highlights “logistics, development times, constantly increasing costs and changing consumption patterns in the textile sector (second-hand, upcycling, etc.)”

Rouje, a role model for influencers?

For these companies to be sustained over time, it is necessary above all “to be able to imagine that someone else can take the reins”, judges Alice Audrezet.

This influencer marketing specialist cites, for example, Rouje, the clothing brand launched by influencer Jeanne Damas in 2016, which is sold online but also at Galeries Lafayette.

“The influencer image is often accompanied by quite a negative judgment,” and people labeled as influencers “often don’t classify themselves as such,” says Joseph Godefroy. “Finally, this rather negative relationship with the term, and therefore with the status associated with them, contributes to their desire to present themselves as professionals in an activity that is not just promoting a product.”

Beyond the financial aspect, these ventures are also an opportunity for creators to show a new face. Jeanne Damas presents herself much more as a fashion designer and businesswoman than as an influencer.

Source: BFM TV