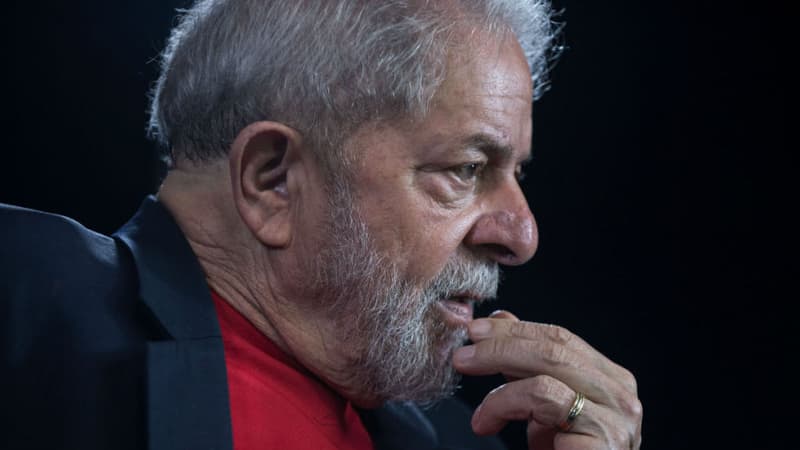

Lula still has work to do. This 77-year-old former metallurgist will begin his third term on January 1, 12 years after leaving power and after spending 580 days in prison, after convictions for corruption that were finally annulled due to formal defects.

Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva was elected president of Brazil on Sunday, obtaining 50.9% of the vote in the second round, compared to 49.1% for far-right President Jair Bolsonaro, after a very tense campaign. But his tenure shouldn’t be much easier than this campaign.

The most immediate challenge is the one posed by Bolsonaro, who had not yet appeared on Tuesday afternoon to formally admit defeat.

• Protection of the Amazon

Lula will also have to repair the damage caused by his predecessor’s policy in the Amazon. During his campaign he highlighted his desire to protect the Amazon rainforest and fight deforestation. The Amazon stretches across nine countries, but the Brazilian part of the jungle is the most important.

After almost 15 years of downward trend in deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon, it has accelerated considerably since Jair Bolsonaro took office in 2019, according to Brazil’s National Institute for Space Research (INPE). The former president’s government has “significantly weakened government bodies charged with monitoring the environment and enforcing laws to protect the forest,” according to Greenpeace. In 2021, deforestation affected more than 13,000 km² of territory in the Brazilian Amazon: this is more than the area of Qatar.

With the end of his term drawing near, the pace has gotten even faster this year. In September, for example, the deforested area in the Brazilian part of the largest tropical forest in the world increased by 48% compared to September 2021, again according to INPE.

• Promised policies of funds

Another great challenge for the new president, at a time when he will have to finance the promised social policies and without the growth of his previous mandates: the finances of the Brazilian State have been weighed down after the distribution, for electoral purposes, of tens of thousands of million reais in aid during his campaign for Jair Bolsonaro.

Lula, for example, promised to exempt personalities earning up to 5,000 reais a month (about 970 euros) from income tax and reduce taxes for the middle class.

In July, a note from the General Directorate of the French Treasury pointed out that the measures taken by Bolsnoraro (allocation for gas, food program) could boost the Brazilian economy in the second half of 2022. The document added, however, that it was also running the risk of leading to “medium-term tax increases to deal with the deteriorating budget situation”.

• A deteriorated social situation

Poverty has increased considerably in Brazil during the pandemic. Between 2019 and 2021, 9.6 million people saw their income drop and joined the group of Brazilians living in poverty. In 2021, 62.9 million Brazilians, or 29.6% of the country’s population, had a monthly per capita income of less than or equal to 497 reais (96 euros), according to a study by the Brazilian think tank FGV Social, conducted with data from the national statistics agency.

The country is also experiencing a food crisis exacerbated by the pandemic. 55.2% of households faced some level of food insecurity in 2020, “an increase of 54% since 2018”, according to a report by Rede Pessan, an independent research center. Food security is, according to the indicator used by the study, the fact of having access to quality food in sufficient quantity and not feeling a threat to the supply in the near future.

• A polarized population

“Half the population is dissatisfied” with the result of the presidential elections, Leandro Consentino, a political scientist at the private Insper University of Sao Paulo, points out elsewhere for AFP. 58 million voters have voted for Bolsonaro. “Lula will have to pacify the country.”

The violence of the campaign fueled this polarization. Bolsonaro insulted Lula: “thief”, “former prisoner”, “alcoholic” or “national shame”. The latter hit back: “pedophile”, “cannibal”, “genocidal” or “little dictator”. Accusing each other of lying, Bolsonaro and, to a lesser extent, Lula, fed the disinformation machine, which worked like never before in Brazil.

There “there are not two Brazils,” Lula declared on Sunday. “I will govern for 215 million Brazilians.”

This did not stop Bolsonaro supporters who refuse to accept his defeat from blocking roads across the country on Tuesday. The federal highway police reported 250 roadblocks, total or partial, in at least 22 of Brazil’s 27 states. As of Monday night, only a dozen states were concerned.

• A Parliament to the right

Lula will finally have to deal with a Parliament that the legislative elections on October 2 have leaned more towards the radical right, with Jair Bolsonaro’s Liberal Party (PL) having become the first formation both in the Chamber of Deputies and in the Senate. .

When presenting himself, Lula brought together a heterogeneous coalition of a dozen formations around his Workers’ Party (PT). He also chose a vice president in the center, Geraldo Alckmin, a former opponent defeated in the 2006 presidential elections, to seduce the moderate electorate and business circles.

Source: BFM TV