HE

This Sunday, October 20, Stanford University announces the death of Philip G. Zimbardo, one of its psychology professors. The establishment praises “the immense contribution” of the man who also called himself “Dr. His most famous work: the “Stanford Prison Experiment.”

What are we talking about? From a controversial experiment carried out in the basements of the prestigious American university during the 1970s. The official objective: to demonstrate the effects of the prison system on individuals, and the relationships of domination established between guards and their prisoners.

But, ultimately, this project demonstrated above all, according to him, the banality of malicious acts, of sadism, among ordinary people, that is, a “Lucifer effect” conceptualized by the psychologist. The disconcerting ease with which anyone can do evil, if given the means.

“It can create a feeling of fear among prisoners”

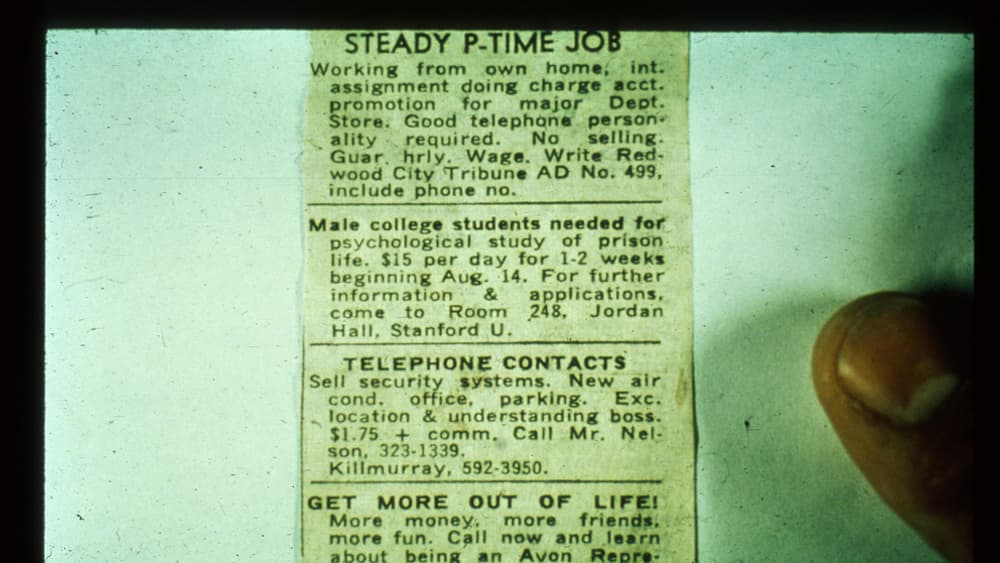

It all started with a small advertisement in the local newspaper. “Male students wanted for a psychological study on prison life: $15 a day for one or two weeks,” reads a few-line supplement.

As Dr. Z related, “more than 70 volunteers” responded to the advertisement. Screening was then carried out to exclude candidates with psychiatric disorders, disabilities or a history of violence.

“In the end, we selected a sample of 24 American and Canadian students who happened to be in the Stanford region (…) In all aspects that we could test or observe, they acted normally,” the researcher said in an interview. Page dedicated to his study, which summarizes dozens of public archives, including video recordings, photographs, etc.

The participants were then randomly divided into two groups. On one side the guards, on the other the prisoners. To immediately put the captives in uncomfortable conditions, they were arrested by real police officers, during a “quiet Sunday morning.”

“The suspect was arrested at his home, charged, advised of his rights, slammed against the police car, searched and handcuffed, often under the surprised and curious gaze of neighbors. The suspect was then placed in the back from the police car and taken to the police station, with all the sirens blaring,” the professor recounted in his own files.

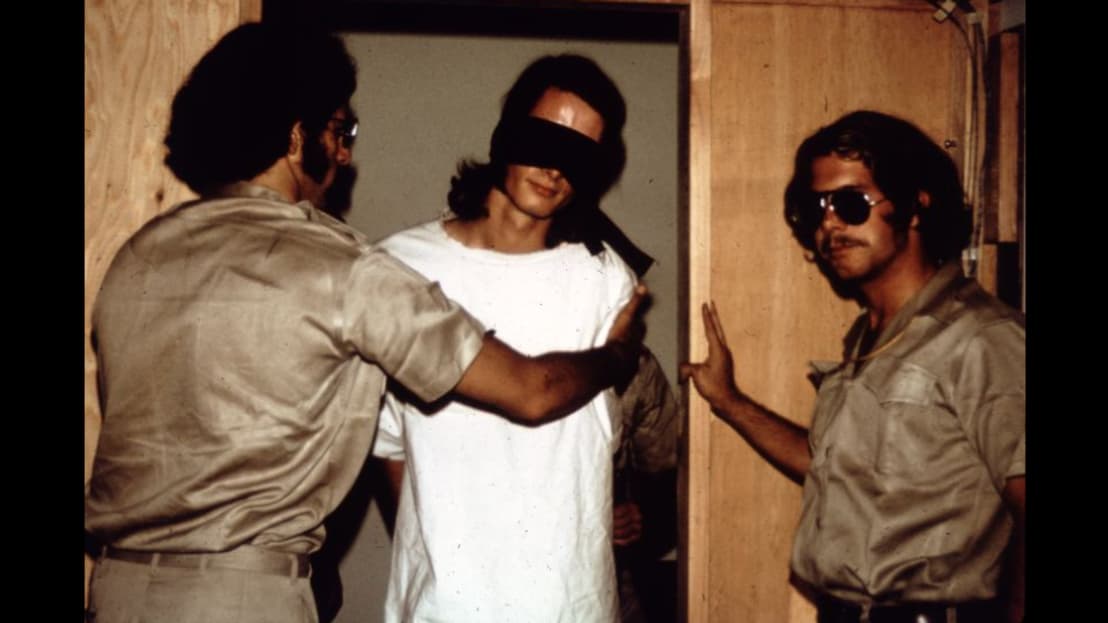

Once at the police station, participants were identified, registered, disinfected and then transported blindfolded to the false prison set up under the campus. An austere environment, made up of poverty cells, a “hole” intended for isolation and a corridor intended to serve as an exterior.

“This corridor, called ‘The Courtyard’, was the only outdoor place where prisoners were allowed to walk, eat or exercise, except to go to the bathroom at the end of the corridor (which prisoners did blindfolded to not knowing the way out of prison).

In this establishment, created with the help of a consultant specialized in the prison environment, everything was designed to destabilize and disorient the participants, without deviating from the reality of life in prison.

On the contrary, everything was done to establish the legitimacy and power of the guards. Dressed in khaki suits, sunglasses and armed with a wooden cane, they had almost all the powers.

“You can create in prisoners a feeling of boredom, of fear to a certain extent, you can create a notion of arbitrariness due to the fact that their lives are totally controlled by us, by the system, by you, by me, and not “You will have privacy…” the scientist told the guards, according to the story of Haslam and Reicher, two psychologists critical of this experiment.

A study interrupted in disaster

Sadistic behaviors, riots, development of serious disorders… In front of the cameras, over the course of a few days, numerous notable behaviors were observed. At night, for example, the guards became violent, thinking that they were no longer being watched.

The “guards” subjected their detainees to numerous humiliations, forcing them to remain naked or to clean the toilets with their hands. Guards inflicted other “physical punishments,” including push-ups.

“Later we learned that push-ups were often used as punishment in Nazi concentration camps,” says the psychologist.

The observational study, which was to last two weeks, was finally interrupted just six days later, given the severity of the behaviors expressed. And even in this period of time, two people with disorders (uncontrollable crying, dark thoughts) had to be taken out of the “prison”, one of them after just 36 hours.

“I felt totally desperate, more desperate than I ever thought I would be,” described the man known as “No. 1037”.

What motivated the psychologist to end the experiment? The reaction of a participant, Christina Maslach, a student who came to observe the scene, offended by the conditions of detention of the study subjects.

The woman who later became Philip G. Zimbardo’s wife was, according to him, the only one who protested among the long list of observers: students, professional psychologists and even a priest. The latter, however, warned the family of a participant of the horror they were experiencing there.

Questionable methodology, accusation of “fraud”

On August 20, 1971, the Stanford experiment ended. For the person responsible for the study, the conclusions are clear, “ordinary students can do terrible things.” However, criticism of this study, from its methodology to its conclusions, was frequent at the time and is equally common today.

In story of a lieResearcher Thibault Le Texier demonstrates that Philip Zimbardo’s involvement distorted the results. “Philip Zimbardo has always stated that as soon as he intervenes in its progress, in a successful scientific experiment, the scientist must not interfere with the results, nor direct the behavior of the participants towards a prewritten conclusion,” the social sciences stated in 2018. Le Temps researcher.

The experiment, impossible to reproduce for ethical reasons, could have led to biased results, according to other psychology researchers, whose research led to different, even opposite, results from those of the Stanford professor. Another participant in the study, a former student, also claimed that it was a “fraud” and “dishonest.”

In the face of these criticisms, Philip Zimbardo asserted during the last years of his life that there was “no substantial evidence that changes the main conclusion” of his study. The experience “serves rather as a warning about what could “It happens to each of us if we underestimate the extent to which the power of social roles and external pressures can influence our actions,” he responded to his detractors. Precursor or scammer? Zimbardo undoubtedly leaves a mark on the history of his discipline.

Source: BFM TV