Some US states have not yet formally abolished slavery or “forced labor” practices. While most forms of slavery have been considered crimes in the United States since 1865, certain exceptions remain, notably in the Thirteenth Amendment to the US Constitution, which specifies that a sentence of slavery may be imposed to punish a crime.

800,000 prisoners work in US prisons, most of the time without receiving a decent wage, or even no salary at all, according to a report by the American Civil Liberties Union.

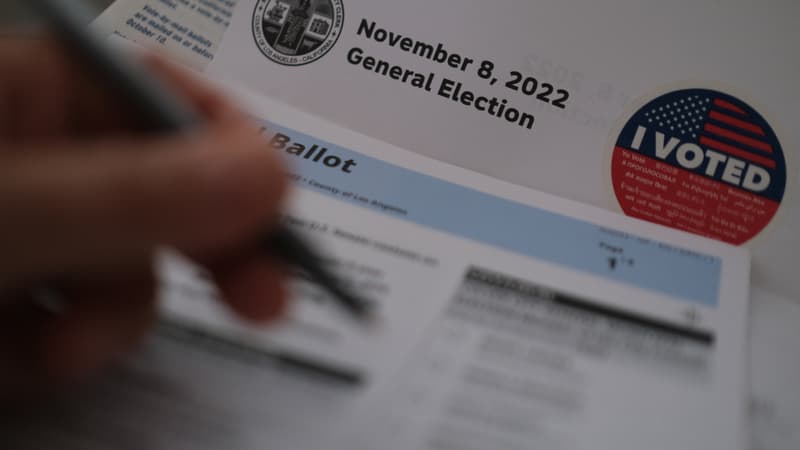

Five states voted

The mid-term elections that took place this Tuesday across the Atlantic were therefore an opportunity for several of these states to propose to the voters to abolish this type of sentence once and for all. In fact, it is common during these elections that Americans are called to vote on local reform projects, in addition to appointing their political leaders.

Therefore, voters were able to vote “yes” or “no” on proposals for the total abolition of slavery or forced labor in their legal texts in five states: Louisiana, Alabama, Tennessee, Vermont and ‘Oregon. Such penalties are still enshrined in the law of twelve other states.

As of this writing, four of the five outcomes are known: Vermont, which allowed forced labor to pay a debt, damages, or fines, as well as Tennessee and Alabama, voted in favor of such abolitions. Louisiana voted against. Oregon remains, where the “yes” wins for the moment but where the count is not over.

Picking cotton for two cents an hour

Slavery and forced labor are more frequently related, in the United States, to domestic tasks typical of prison establishments, indicates Claudia Flores, a researcher at Yale University, in New York Times. By not using employees who must be paid minimum wage for tasks such as catering or laundry, administrations can benefit from reduced operating costs.

But inmates can also work for outside employers, particularly in the manufacturing industry (school supplies, tuition, textiles, etc.), but also in agriculture.

A former prisoner tells the New York Times he was paid two cents ($0.02) an hour to pick cotton and vegetables in Louisiana fields during his years of incarceration. He explains that he worked in intense heat sometimes without being able to drink. Frustrated and angry, he would have gotten hurt so he wouldn’t have to work anymore in these conditions. A behavior sanctioned with a transfer to solitary confinement in his prison.

The ACLU estimates that the 800,000 people who work while incarcerated in the United States produce more than $2 billion in goods and more than $9 billion in services a year, while being paid an average of 13 to 52 cents of time. The prevailing minimum wage in the traditional American job market is, by comparison, $7.25 an hour. Some states like California, which still have forced labor penalties, have even raised this threshold to $15 an hour.

Abolitions that have few consequences

If the abolition of slavery is supported by progressive activists with the aim of allowing decent remuneration for detainees, several jurists have explained in particular to the New York Times that votes for a formal abolition of slavery would certainly not have an immediate effect, if at all. They could be challenged in court and/or invalidated by the vote of local legislators because they do not always have binding values.

These votes, however, carry a symbolic weight: those who campaign in favor of these abolitions want to remember that slavery has not been completely abolished in the United States and to create a propitious political and media moment to give visibility to this debate at a national level. table. Democratic senators had attempted to amend the constitutional amendment authorizing the federal condemnation of slavery in June 2021, but found insufficient support to pass the amendment.

Three states have already voted to remove the slavery conviction from their legal paraphernalia: Colorado in 2018 followed by Nebraska and Utah in 2020. The fallout has been minimal: Colorado recently fired an inmate citing his newfound right not to be forced to work, while a prison in Arkansas awarded wages of $20 to $30 per week to inmates who had previously worked without pay.

Some observers also explain that in the event of the total abolition of forced labour, prisoners who could acquire skills, benefit from the feeling of being useful and even earn a little money, could be deprived of work. Facilities could then use outside employees to perform tasks previously assigned to inmates if they have the means, instead of directing these expenses to inmates. But if they lack funds, it is simply the living conditions in the prisons that could be further degraded, due to the lack of personnel to carry out certain tasks.

Source: BFM TV