A few steps from the Louvre pyramid, below the Museum, a stairway almost imperceptible to onlookers and tourists leads to the “C2RMF”, a barbaric abbreviation for the Center for Research and Restoration of the Museums of France. Two-meter offices under which researchers of multiple nationalities meet but with a single objective: to better understand heritage.

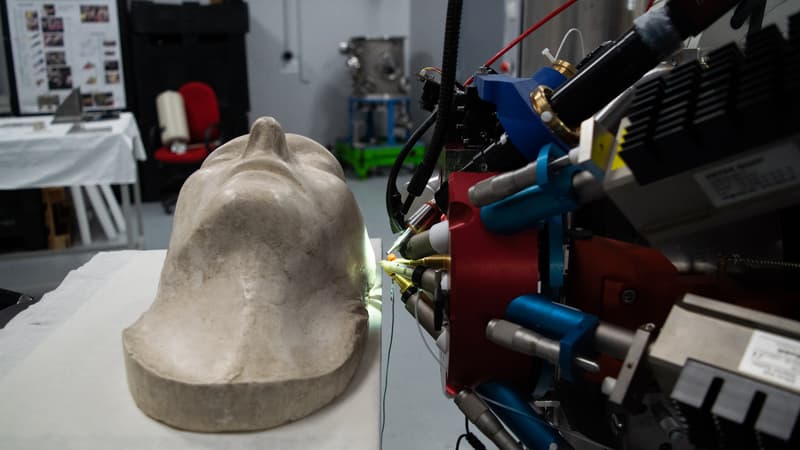

Around the corner of a maze of stairs and corridors, Quentin Lemasson, an employee for 12 years at the research center, welcomes you to his lair. “Shall we show you the machine?” asks the chemical engineer, with a sparkle of excitement in his eyes. The machine is AGLAE (for Accelerator Grand Louvre of Elementary Analysis), and it is impressive.

only one in the world

At 27 meters long and weighing five tons, AGLAE is a unique particle accelerator in Europe, as it is the only one dedicated entirely to the study of heritage. The machine makes it possible to generate proton beams at nearly 30,000 kilometers per second to understand the exact composition of a work and ultimately reveal its mysteries, particularly its origin, in just a few minutes.

What happens between these two stages then belongs to the most elementary physics and chemistry for specialists and to the most abstract for novices. In this way, the device allows the collection and storage of millions of data used by researchers around the world.

Above all, all this work allows us to clarify some parts of history that have remained secret or unexplored. The example is made with accounts that are currently being examined by Spanish researchers. These green pearls, ranging from jade to turquoise, were found at Carnac in Brittany.

However, its origin is far from the Emerald Coast, but rather on the Castilla side of Spain. Without these analyses, it is obviously impossible to know the existence of commercial exchanges between the Spanish mines and the Bretons during the Neolithic (around 5000 years BC).

Bringing the past to life

A few halls away, Charlotte Hochard is occupied in a much smaller space than her colleague. A narrow, cold and noisy room, where the 3D engineer has been busy since 2017 analyzing old wallpaper and dilapidated walls with scanners.

Thanks to the decomposition of light, it is possible for him to see the depth of the line and the screen of the paper to know its origin. “This technology allows us to work on elements that are invisible to the naked eye, whether due to light, colors or perception”, explains Charlotte Hochard.

On the walls, these scanners and 3D imaging machines can, above all, allow drawings erased by time to be revived. This is what happened when Charlotte Hochart worked on the site of the Château de Selles in Cambrai.

The stone walls, which housed noble prisoners, are covered in engravings, texts and pictograms, stacked one on top of the other and almost obliterated for some. “Before, archaeologists made what are called profiles, by hand. Now the machine does it for us by calculating exactly the depth of each line.”

In addition to rediscovering and reading these engravings, scanning also makes it possible to preserve the history and heritage of this region, which is gradually being erased and disappeared. A duty of memory, in a way. For example, technology has also allowed an archaeologist to extract the traces present in the walls of certain concentration camps. A job that especially affected the specialist due to the messages that arose.

“Decarviarder” to better decipher

However, it is not only in the Louvre that the scanners have revealed mysteries. On the National Archives side, the exhibition “Louis XVI, Marie Antoinette and the Revolution” covers the period after the events of 1789. But the attraction of the exhibition is based above all on the “stripping” of fifteen Letters of Marie Antoinette to the Count of Fersen.

Because out of “diplomatic prudence”, the Count had taken the habit of “censoring” some of the letters received, that is, adding lines to the Queen’s writing to make it unreadable for anyone. unconventional epistolary correspondences. Unfortunately for Fersen, two researchers managed, within the framework of the “Rex project”, to defy the laws of the elements.

By using the XRF scanner, which is more dedicated to archaeology, they were able to identify the composition of the inks present in the paper and differentiate between classical writing ink and opaque ink. However, deciphering the secrets of the story requires patience, as it takes 40 hours of work to scan a single line.

Censuses using AI

Rereading the indecipherable is also the mission of the Socface project, carried out jointly since the end of 2021 by researchers from archive services, language and information processing, and researchers from the social sciences. The goal? Gather in a single database the population censuses of the 100 departments, from 1836 to 1936, that is, several million handwritten data.

A titanic job that is based on the ever-increasing performance of handwriting recognition artificial intelligences, used here to decipher line by line and column by column the names, professions and other places of birth of the French inhabitants and to compare the sources.

“The century of French history that Socface is interested in is marked by spectacular changes: urbanization, industrialization, demographic transition… The aim of the project is therefore to analyze at the micro level the individual trajectories of each inhabitant throughout his life. life”. explains to Tech&Co Lionel Kesztenbaum, a researcher at the National Institute for Demographic Studies who is working on the project.

But the Socface project presents another interest, for the general public: a search engine, soon accessible to all, in which it will be enough to type a surname for the AI to do the search. A real breakthrough that will benefit genealogy enthusiasts. Christopher Kermorvant, another thinking head behind the project, however, recalls a limit inherent to this technology: “There is an error rate of between 5 and 10%.”

Beware of overinterpretation

But isn’t there a risk of staining the memory of these works, documents and other archives, when you constantly seek to better understand and decipher them? Frédéric Rose, president of IMKI, a company specializing in artificial intelligence, tends to qualify the use of AI in the rediscovery of history.

The company is, in particular, at the origin of a speech by Robert Badinter 2.0 that mixes deep-fakes, current shots and archive images. A project that meant recovering the memory of the moment and giving it back its sublime, being the television images of the 80s and 90s, according to him, “the worst”.

“Artificial intelligence improves and gives details that we do not have. But AI has done its job so well that it has tended to morph too much. It must be used without turning it into the unreal and losing the nature of the object. ChatGPT, when it doesn’t have the answer, makes it up. And all generative AIs work like this. It is a danger”, criticizes Frederic Rose.

Improve collective and historical memory without staining the support and memory. A great challenge that awaits researchers and specialists in the coming years, since the race for technology is in full swing, without skimping on any area.

Source: BFM TV